“Now that is the sound of a very, very busy weaving schedule,” says David Gallimore, the managing director of The Luxury Fabrics Group, as he flings open the door of what is effectively the Bradford company’s engine room, causing a tsunami of sound like the clackity-clacking of a thousand old-fashioned typewriters to wash over those present.

“Nearly all the machines are running as this is a particularly busy time in terms of batches of cloth going to the Middle-East, which is our third biggest market after Italy and Japan.” It’s no surprise that the machinery in these cavernous rooms – much of it, incidentally, made by former German warplane manufacturer Dornier – is in overdrive throughout Luxury Fabrics’ 6am-10pm operating schedule, given how many brands, all boasting impressive heritage and cache, operate under its umbrella. The John Foster Brand, founded in 1819, took plaudits for its alpaca and mohair fabrics at the Great Exhibition of 1851, while William Halstead, which moved here in 1877, is a weaver of fine worsted wools, supplying the giants of international fashion.

Kynoch 1788 is a division Luxury Fabrics that operates from Lymehall in Scotland whose staff, during World War I, would gather sphagnum moss from the local area, drying it in the rising heat on the spinning department floor then send it to military hospitals to be used as bandages and wadding (moss has anti-bacterial properties). Charles Clayton, Reid & Taylor and Selka are also in the mix, with the entire stable now branded under the name Standeven. In 2016, meanwhile, an exclusive partnership was formed, adding the rare and luxurious wool gleaned from Escorial sheep grazed in Australia to the company’s repertoire. The Escorial sheep is only three quarters of the size of a Merino, so the yield is lower, but its corkscrew fibres make for excellent resilience and stretch.

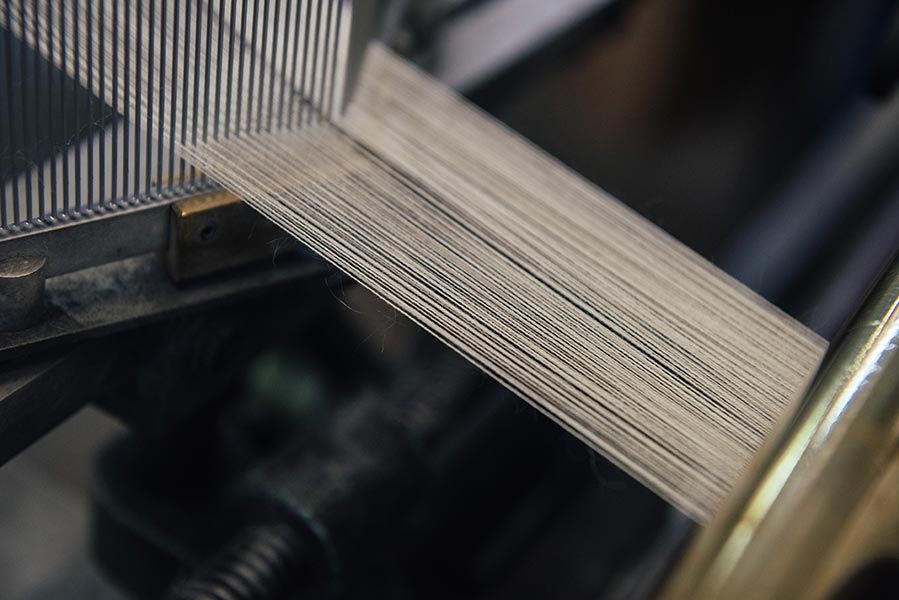

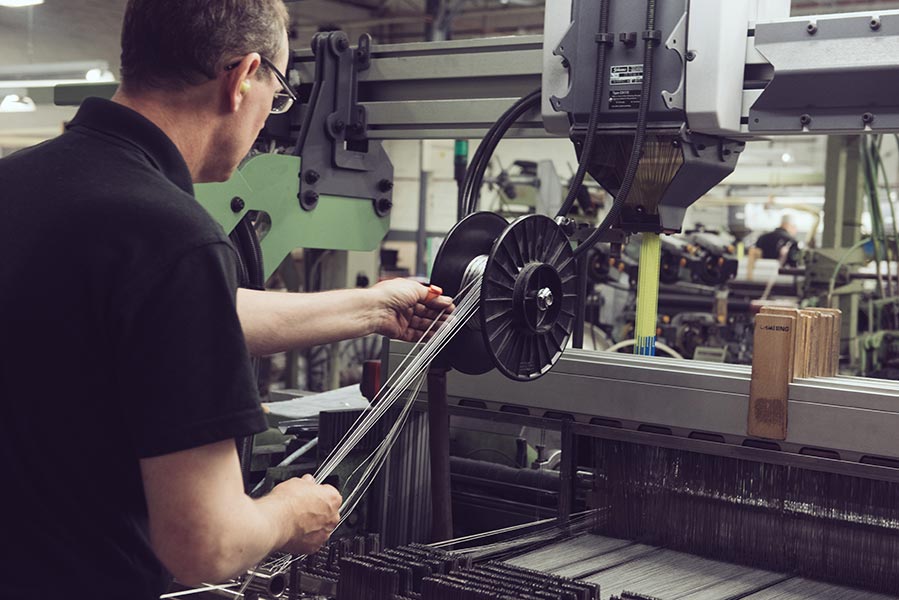

Gallimore leads us over to just one of the many sources of noise, a warping machine which is being fed by threads from a vertical wall of creel-mounted bobbins. A single warp will usually have around 5,000 ends – less or more than that number in cases of coarser or finer yarns respectively – so they’re committed to the warping drum in increments of 200 ends before being rolled off onto a warp beam: a process also known as section warping. The whole process is monitored by eagle-eyed, highly experienced staff: “Precise angles and tensions are critical throughout warping and weaving,” as Gallimore points out.

But the role of precision here comes home to roost in the next room along the production chain, in which we see complex patterns – houndstooth overlaid with broader checks in one instance – come to fruition on the looms. The interaction between the in-house designers and the looms is a perfect dichotomy of creativity and meticulousness. A pattern having been settled on, complex mathematical sequences dictating how the weft ends will interlace with the warp ends are written out by hand for machine operators to programme from, while a peg plan – the principle of which calls to mind a self-playing fairground organ’s pinned barrel – informs the order in which each shaft should lift, and to what height.

The resulting fabrics are afforded wonderfully emotive names, which have semantic as well as evocative resonance: “Black Storm is for formal eveningwear, whereas Park Lane is for a traditional Super 120s urban suit,” explains Gallimore. “With Snowdonia, we were trying to think of a name suited to winter coatings, things you might wearing going up a mountain…”

Finally we enter a mending room, where a team of BinoMite-wearing darners – custodians of another ancient craft within the wool-processing sphere – are taking perfectionism to borderline-obsessive levels. “The need to mend flaws is an inevitable aspect of working with a natural fibre,” says Gallimore, gesturing to a row of workers darning miniscule, wispy slithers of loose fibre back into the cloth. “They’re making sure the fabric is clean, free of contamination and flawless.”

A committed wool aficionado, Gallimore is passionate about the merits of operating in the traditional heartland of Britain’s wool industry. “For us it’s a case of ‘Why would we be anywhere else?’” he says. “The founding fathers of these textile businesses were the people in the thick of the industry revolution; they were the ones whose employees were on the gates with pitchforks and batons trying to stop Luddites from coming in and breaking up the new machines. This is where it all started: Bradford was the city of wool.”

Gallery

The reasons underlying this, he says, are similar to those behind certain wines being cultivated in certain regions of the globe. “When we talk about fine winemaking we talk about soil, conditions, terroir,” he says, “and one of the reasons why Britain’s wool textiles industry is based here can be seen just by looking through the window: the atmospheric conditions. Before we had air-conditioning and dehumidifiers, the natural atmosphere here – thanks to being this side of the Pennines – is just right, in terms of moisture content, for processing wool. It’s not by chance that this side of the Pennines is wool and the other side is cotton.”

Luxury Fabrics currently employs around 250 people, and getting young workers enthusiastic about wool is a major priority when it comes to its plans for organic growth. So, they were delighted when the collective sense of passion here received a shot in the arm recently. “We’ve just had a Royal visit – the Royal Highness Princess Anne, the Deputy Lord-Lieutenant, the High Sheriff, the Lord Mayor – and what that did for our staff was fantastic,” says Gallimore. “It really lifted them, because we don’t always get to talk about how proud or passionate we are. The visitors were all walking around asking questions, showing a genuine interest and so on - there were a lot of chests proudly puffed out. Staff felt like their skills and experience were being truly recognised.” The skills and experience he alludes to are rare and hard-earned indeed, and we have many generations to thank for them.