Take a drive through Scaddan’s ‘Red Gully’ and you would see a vast contrast between lush pastures and desert-like eroded sand hills. In reality, this is the unusual landscape that Australian woolgrower Dave Vandenberghe chooses to work on.

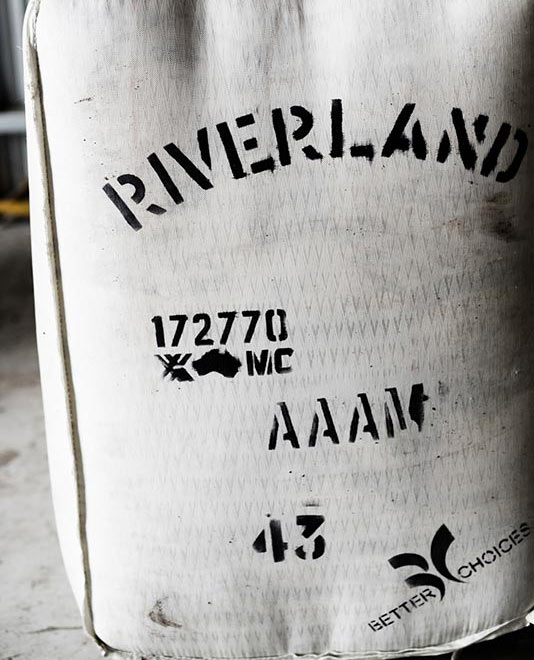

‘Red Gully’ is a 1850 hectare property on the southeast coast of Western Australia, near the town of Esperance. Not all that far from the turquoise blue water of the Great Australian Bight, this wool-growing property – which makes up part of the larger 5500 hectare property ‘Riverland’ – is a far cry from the lush green landscapes often synonymous with the Australian wool industry. This sandy property may not look much to the untrained eye, but to a passionate woolgrower like Vandenberghe, potential was seen, and reward is slowly being reaped. Running about 7000 Merino sheep, ‘Red Gully’ produces luxurious Merino wool averaging 18 micron that’s used in next-to-skin apparel and fine tailoring. But it’s the behind-the-scenes work in producing this premium fibre which makes the final product even more remarkable.

(Left) Dave Vandenberghe of Red Gully.

Parts of the sandy paddocks of Red Gully pose a problem, as they don’t retain moisture and it becomes near impossible to grow any pasture for the sheep feed on. And so Vandenberghe embarked on a process of soil rebuilding to turn sand into feed. “The majority of our farms are clay, so when we purchased ‘Red Gully’ it gave us some major challenges,” he said. “Thirty per cent was fairly degraded; some parts were good, but there was a lot of sand erosion and areas that were unproductive. I think my bank thought I was a little ambitious,” he mused. “Rainfall is 400 millilitres and falls mainly in winter in this Mediterranean climate, but we can also have wet summers from either cyclones or storms. Strong winds also pose a problem for fragile soils.”

Non-wetting soil was the largest issue. This was deep sand which held no moisture or nutrients and very little organic carbon. In each paddock there was a balance of good soil, deeper sand and highly eroded, degraded areas making grazing and cropping difficult to manage. However, Vandenberghe was up to challenge of improving his land and the health of the environment. The first step was to identify areas of the paddocks with sand deeper than 700 millimetres and to level these areas to create a flat surface.

Stage two was to spread clay with what’s known as a carry grader, spreading between 450 tonne of clay per hectare up to 1000 tonne on the blowouts caused by wind. Thirdly, the paddocks were deep ripped – a process to aerate the soil – to reverse the compaction and allow plant roots into the subsoil. “This is followed by the incorporation of the clay to a depth of 300 millimetres to ensure the soil is ready to hold both moisture and nutrients. The prepared paddock is then seeded with barley to stabilise the soil and prevent wind erosion and hopefully recoup some of the cost. Finally, in the following summer, the barley stubble cover is seeded with pasture.”

Thanks to the similarities of the Mediterranean climate, French serradella is the preferred pasture as it is a nitrogen-fixing legume, deep-rooted and hard-seeded. “It is also fantastic for grazing Merinos, with many added health benefits for them. Serradella will continue to persist well into the summer, staying green far longer than most annual legumes. With a root depth of two metres this allows the serradella to access fertilizer and moisture deeper in the profile, thus reducing recharge of water levels. Legumes, while fixing nitrogen from the air, also increase carbon levels in the soil. As a result, soil will improve each year and become more productive.” Bit by bit, Vandenberghe is slowly turning sandy paddocks to productive land. “I have set a goal to finish the whole farm within ten years and we are currently in our third year.”

And while the bank may very well have thought Vandenberghe to be a little optimistic in his venture, the proof really is in the pudding, with Merino sheep now happily roaming the paddocks on this regenerated land. Like every other Australian woolgrower, Vandenberghe believes it’s important to leave the land in a better state than how you found it. “It doesn’t sit well with me to leave degraded areas for future generations. We have to look forward to 20 years’ time as to what the farm will look like. And it is a challenge to turn something unproductive into something productive and add value to the land.

But it makes it a lot better place, both environmentally and aesthetically. I could fence it off and ignore it – but I know it’s there and I just want to restore the land. That’s my challenge; as a custodian of the land I want to improve it for future generations. We’re in the spotlight of the world, and we need to put our best foot forward. We are doing something positive and proving it is possible to rehabilitate the soil into productive land for the future.”

Proud of what he does and the fine wool he produces, Vandenberghe is a true believer in the infinite potential of the fibre. 100% natural, renewable and biodegradable, Australian Merino wool is loved the world over by designers who are presented with a blank canvas when working with wool. Superb next-to-skin softness, moisture management, odour resistance and natural elasticity - no other fibre, natural or man-made, can match all of wool’s benefits, making it the ultimate ingredient for luxury apparel and technical performance wear.

“Australian Merino wool is most unique; we have the best in the world. I think the world needs to look at Merino wool production in a different light. It is so much better for the environment than the petro-chemical plastics we're wearing. Merino wool isgood to wear and is slowly becoming a staple in modern fashion. As such an environmentally friendly product, our sheep co-existing in our farming system, and adding to the improvement of the environment, is a win-win for woolgrowers, environmentalists and the fashion industry.”